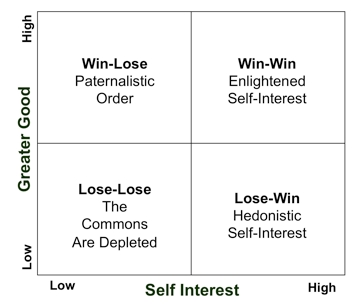

In a 1968 Science article, ecologist Garrett Hardin proposed the Tragedy of the Commons as an explanation for why otherwise reasonable and self-interested parties would destroy shared resources they each depended upon. In the absence of rules and consequences that dissuade others from “over-grazing” the metaphorical commons, each player has little choice but to do the same. Short-term interests, fear, and greed undermine the parallel imperative to invest in a healthy and viable future. Inevitably, win-win scenarios become win-lose and then lose-lose as the grass or oxygen or ozone or peace we all need disappears.

The Commons metaphor turns on the core dilemma – self-interest versus the greater good. Do I pursue my goals without concern for the well-being of the larger community, or should shared needs always take precedence over those of individuals? Showdowns are happening in every corridor and at vastly different levels of scale. Globally it’s around access to land, clean water, peace, wealth…you name it. Nationally we see the same dynamic affecting central issues like provision of health care and utilization of transportation infrastructures. Systems are pushed beyond their capacity, and the response of too many self-interested stakeholders is to take more, not less – to add to health care costs, to contribute their small bit to worsening gridlock and pollution.

Figure 1 © Transcend Strategy Group 2012

Population growth, urbanization and technological advances are making us more interdependent than ever before, increasing the frequency and costs of these conflicts. How do we encourage people and nations to “raise their game”, to think about long-term consequences and shared interests?

It is time to crack the code on enlightened self-interest.

The debate about how to do this usually takes the form of whether to impose rules and sanctions or to trust self-organizing forces to maintain a sustainable equilibrium; government enforced intervention versus the freely operating forces of communities and markets reaching balance through self-regulation. Experience teaches that it is rare that one or the other of these approaches is sufficient, so the question becomes, what will help to mediate conflicting interests in situations like these?

Ultimately, we need to sever the illusory conflict between individual interests and those of the community. Increasingly, they go hand-in-hand: two sides of a complex whole. The faster people realize this, the less damage that’s done and the sooner good planning and repair work can begin. What breaks the logjam and allows people to transcend their either-or…win-lose …position is caring that is both thoughtful and compassionate. Reaching the point of informed caring happens in many ways, often quite naturally. Unfortunately, we are also very capable of resisting and avoiding this realization.

Here are five suggestions for how to encourage parties to break the bind of The Tragedy of the Commons:

1. Identification – when we objectify the other as separate from us, our family, tribe, whatever…it’s easier to not care about their fates. Constructively reframing this may take some creativity; each situation is unique. We need to care about the well-being of others and feel their losses as real and important. The NIMBY syndrome (not in my backyard) and the depersonalization of enemies allows bad things to occur without triggering the outrage and opposition we might expect. It’s not us versus them; it’s all of us together.

2. Transparency – seeing reality, having access to facts, #s, etc.. in real time allows us to know what is going on and to trust what we know. My old partners Don Tapscott and David Ticoll wrote in their book, The Naked Corporation, “If you’re going to be naked, you better get buff”. In an increasingly transparent world, there’s nowhere to hide your improprieties, and the chances of getting caught are much higher. This makes us more accountable, and in a positive sense, it influences us to pay a little more attention to our decisions and actions. Transparency breaks the game-theory standoff that escalates self-interested action taken in self-defense, just in case the other guy isn’t playing by the rules.

3. Understanding – people need to understand what is at stake and the ramifications of pursuing their self-interest. We can choose to alter our actions if we see the logic and benefits of one course of action over another. Decision-making in situations like urban development and the construction of pipelines can be counter-intuitive, and benefit from careful analysis and consultation. For example, population density (up to a point) turns out to be environmentally positive, reducing the need for cars and increasing the return on a shared public infrastructure.

4. Confidence – there needs to be a viable and acceptable option, and a path for getting there. Even if imperfect, we usually require more than “trust us” to change hard held positions, especially when there is fear and uncertainty. Leadership counts; being concrete and explicit is important. The next few steps need to be named. Without that, tribes will wage war against neighbors and overuse of scarce and non-renewable resources will continue unabated.

5. Accountability – we do some questionable things when we believe no one notices or cares, from online lurking to hand-washing in public washrooms (apparently much less frequent when alone than when someone else is there). Build a public, sharing aspect into the process, so others witness the decisions and actions taken by individual players. This can be tricky, as we are seeing with international agreements for peace and preservation of the environment. It is working a little better in the financial management of countries, witness positive pressures being applied to countries in the troubled European Community. Accountability is key, but it only works when it is enforceable and where the first four conditions are met.

While not easy, the five pieces provide a practical template to follow where Tragedy of the Commons conditions exist. There are many success stories to draw upon, and more waiting to happen.

Comments are closed.