“I never believed in costly frontal attacks either in war or in politics, if there were a way round.” –Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, was famous for his political flexibility. He changed positions on major issues during his career and was willing to compromise with a shifting cast of political partners in order to gain strategic advantage. And, he was very successful. He was England’s Prime Minster from 1916-22 and perhaps the UK’s most influential 20th century politician.

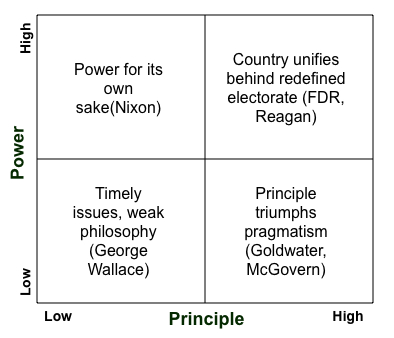

In the battle between holding fast to principles or occasionally bending one’s beliefs in order to acquire power, you could say that Lloyd George bent. His career points to a crucial political dilemma, one that challenges all parties and candidates, and especially today’s Republicans. It’s the dilemma of power versus principle. Strong principles are a virtue but a party that cannot gain power cannot enact its principles into laws.

Voices inside and outside the Republican party are now saying it needs to be a bit more like Lloyd George. It needs to moderate its positions–or take new ones–on a wide range of issues such as women’s rights, gay marriage, immigration, guns, regulations, and budget tradeoffs. They fear that principled intransigence on these issues may alienate women, minorities, young people, and recent immigrants. They want an inclusive “big tent” party. Without those voters the party risks becoming too white, too old, too male, and too rural to lead in the future. Rand Paul recently said “I think Republicans will not win again in my lifetime for the presidency unless they become a new GOP, a new Republican Party,” during a speech in which he advocated an end to the war on drugs.

The Battle Rejoined

The tension between power and principle, and between Republican pragmatists and conservative true believers , has gone on since at least the end of World War II. Republican Presidents Eisenhower, Nixon, Ford and Bush I are generally considered more pragmatic, appealing to the middle of the political electorate. Reagan and Bush II are generally the icons of those who argue for more principled party positions and less compromise.

A political party needs principles, and a vigorous vision, but it also needs to win elections. Lloyd George avoided head-on ideological assaults on his opponents, dismaying fans of unyielding principles. But by the time his career was over, his liberal welfare state vision for Britain, as well as numerous other legislative and foreign policy initiatives, had become reality.

Examining Power Versus Principle

Power: The ability to affect the course of political events or more specifically, the degree to which a party can elect enough people to make key parts of its platform into law.

Principle: The fundamental truths that serve as a political party’s foundation. The degree to which a political party (or candidate) adheres consistently to a set of inviolate principles and positions.

Upper left: Power without principle. Political parties and individuals are prone to pursuing and using power for it’s own sake, ultimately undermining their voter support and themselves. Richard Nixon took positions as an antiwar candidate in 1968, when he had zero plans for ending the conflict in Vietnam. By the end of his term in office his administration was exposed as unprincipled, and even criminal.

Lower Left: Low Principle, Low Power. Parties whose platform is unclear or that latch on to a galvanizing issue without a strong underlying philosophy may last for an election or two but will soon fade. George Wallace, who tapped into anger over racial integration in the US in the 1960s, was such a candidate.

Lower Right: High Principles, Low Power. Presidential candidates Barry Goldwater (R-1964) and George McGovern (D-1972) both suffered landslide defeats at the hands of pragmatic candidates who were seen as less extreme and more centrist in their views.

Upper Right: High Power, High Principles. Parties that win consistently do not merely reflect the midpoint of the electorate. They redefine it. They reposition the middle. This is what Reagan did in the 1980s and what Roosevelt did in the 1930s. They had great skills at working with others and sometimes compromising, but they also had a distinct vision, embedded in core principles, that drove their base of supporters. As with Lloyd George, their skill was reaching out to enough voters in the middle to gain effective power, while keeping true to a set of core principles that animated their most loyal supporters. By doing so, they reset the boundaries of the political middle for decades after they were in office.

Coda

Archetypally, power versus principle is often described as a contest between means and ends. Do the ends (power) justify the means (watering down the party’s core principles)? Conservatives such as Senator Ted Cruz (R-Texas) say no. They believe that by holding fast to principles they will succeed like Reagan rather than fail like Goldwater. Republican primary voters in the next election will provide the answer.

Want More Info?

Here are two interesting debates on this issue.

1. GOP Must Seize The Center

2. PBS commentary from David Brooks and Mark Shields

Comments are closed.