Readers around the globe have recently been presented with a harsh rebuff of Afghanistan president Hamid Karzi’s choice of Mohammed Quassim Fahim as vice-presidential running mate in the upcoming election. Fahim served in this capacity once already (2001 – 2004), and was dropped as controversial. He has a checkered past as a top commander in the militant group Jamiat-e-Islami during the 1990’s civil war, and is believed by some to have illegal, criminal involvement to this day. The group Human Rights Watch has been documenting abuses in the country for years, and is aghast at the announced alliance, saying with this choice Karzai is “insulting the country”.

In the face of such vociferous, predictable condemnation from abroad as well as within his own country, what would lead Karzai to pick Fahim? The reporting in the AP article we read doesn’t ask this question, but arguably it should and so should we all in making sense of the decision.

We all know that ruling in a country like Afganistan at a time like the present is fraught with risks and that scant rewards are available. The question the leader needs to ask is what is the core dilemma I need to address to make a difference in the situation; where do I focus my and my country’s available resources?

![]()

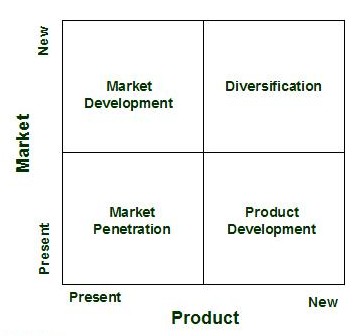

One dilemma that captures the moment and explains the “curious” political decision is the need to promote well-being, peace and improvements on the one hand, while on the other, growing and maintaining credibility and influence. As the matrix above depicts, inherent tensions make this a dangerous and challenging pursuit. Lean too far in one direction and you are seen as unsuitable for the mission at hand. Lean the other way and you will be mistrusted by your own people or the other countries who care about the direction of local events.

This tension between pursuing progressive change versus establishing trust and credibility is of course endemic to volatile transitional situations like we are witnessing in Afghanistan. Others that come to mind are Palestine (Abbas versus Hammas) and Sierra Leone (post- civil war “blood diamonds”).

Identifying the core dilemma does not “fix” anything, but it makes it possible to work on the right issues in the most helpful way. It brings honesty and integrity into the process. It creates a shared understanding and vocabulary for parties to dialogue and be understood.