The recent acquisition of Sun by Oracle brings to a close a chapter of computing history. In the early ‘80s Silicon Valley was home to dozens of small Unix workstation makers. Sun was the only one to survive, growing to become the leading Unix company. Its servers were noted for reliability, and the big software makers, including Oracle, focused on writing software to run on Sun’s Solaris operating system. Ironically, Sun was an early supporter of the Internet and visionary in its approach to network computing. But the combination of the Internet and open source software, in particular, were the source of Sun’s decline.

More than a decade after open source software began acquiring market traction, it still poses difficult questions and dilemmas for IT firms. Initially, it was scoffed at by the software industry, and companies like Sun tried to discredit Linux as unsafe and incomplete, hoping to deter further adoption and defection from their own proprietary offerings. Microsoft was equally disdainful. Bill Gates was quoted in a 1998 PC Week article as saying, “Like a lot of products that are free, you get a loyal following even though it’s small. I’ve never had a customer mention Linux to me.” Within a few years, though, Microsoft heard from loads of customers about the open source threat, and was forced to open some of Windows source code to outside partners.

The early, sometimes fearful responses to Linux took an understandable but narrow and one-dimensional view of the situation, regarding it as a worrisome problem which needed to be removed. “Linux is a threat to our pricing. How can we compete with free?” or, “Linux is giving away knowledge of high economic value that industry has invested heavily in creating. This is not right or fair.”

Time proved that open source was here to stay, and arguably for the right reasons: it made superior use of networked intelligence for creating and realizing value. Companies throughout the computer industry and even some beyond it would have been better off to regard the emergence of Open Source software as a dilemma to understand and exploit rather than a problem in need of a solution. Some did. Start-ups like Red Hat prospered by creating new offerings or supplying services needed by Linux users. Resourceful software firms capitalized by building new products directly on the Linux OS. But the transition proved much more difficult for the large, established incumbents who tried desperately to hold on to or grow existing revenues, while adapting to a new model which gives away much of the product, in order to increase innovation and widen the market.

In that class of corporate titans, there were a few who adjusted their approach fast and prospered. Notable among the beneficiaries was IBM, which understood early on that the dramatically lower cost of Linux and open source applications increased demand for commodity server hardware, installation and services. The company saw Linux as an opportunity to establish new leadership and perhaps weaken competitors dependent on proprietary solutions. Sun, of course, later embraced open source, opening its OS and leading the Java community of developers, but never adequately addressed Linux’s impact on its proprietary hardware and OS business.

(For a quick economic analysis of open source as a complementary good that increased demand for IBM’s services read Joel On Software.)

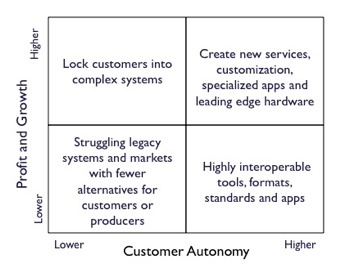

IBM’s ability to adjust quickly and well to open source lies in how they framed the situation. Open source was not an annoying problem to solve or eliminate; as a legitimate challenge to the way the industry operated, it represented a dilemma that redefined roles, relationships, value creation processes and business models. By understanding the opposing forces at play and their implications, they could see the competitive landscape more clearly, and make better choices. The 2 x 2 matrix below is one plausible and constructive way to render the open source dilemma:

Mapping Profitability versus Customer Autonomy – Building a better mousetrap usually costs money and involves risk. While some innovators are motivated to share their ideas freely, businesses have a legitimate interest in protecting their ownership rights and making a profit. The tension between achieving profit and enabling the autonomy that customers want is on the surface only increased by a movement whose goal is to create openly and provide access to all. (Consider the tremendous loss of value by copyright holders in the music industry. Even today 90 percent of all downloads are illegal.)

By becoming leaders in the Open Source movement, companies like IBM and Red Hat found ways to collaborate with autonomous customers and strategic partners while still making a profit (upper right in our diagram). Their strategies and business models differ, but each has grown its business by giving customers greater direct access to the information and software they need to improve their businesses or lower costs.

On the other hand, customers are increasingly skeptical of proprietary products that lock them into technology directions that are determined by a single vendor (upper left). Proprietary software vendors have been forced by customers to make their products interoperate with open source offerings. Even Apple, a stellar example of a proprietary shop, has found its greatest success since adopting industry-standard Intel processors for its computers, and making hardware/software products such as iPods, iPhones and iTunes, which interoperate across computer platforms.

A new challenge for proprietary operating systems may be brewing in Acer’s announcement that it will install Google’s Android, a software platform originally designed for phones, on its small netbook computers. If netbooks, which sell for around $300, become increasingly popular, it will be difficult for software firms to charge customers hundreds of dollars more for operating systems and applications. By going with an open, free OS, Acer hopes to build market share quickly, at the expense of software profits.

A new challenge for proprietary operating systems may be brewing in Acer’s announcement that it will install Google’s Android, a software platform originally designed for phones, on its small netbook computers. If netbooks, which sell for around $300, become increasingly popular, it will be difficult for software firms to charge customers hundreds of dollars more for operating systems and applications. By going with an open, free OS, Acer hopes to build market share quickly, at the expense of software profits.

The tension between ownership of value and customer control is not limited to the software industry. The combination of free information, transparent source code, and a global network of voluntary contributors is upending fields from media to biotech, and lessons need to be found and shared for the interests of all parties. We’ll look for those answers in future columns.