We love our heroes. We hate to see them fall, but when they do, they fall twice as hard. Lance Armstrong’s achievements as a cancer survivor, competitive athlete and fundraiser place him in a rare class of his own. Revelations that he (may have) cheated to win, and pressured his teammates to do the same, are disconcerting. Graced with remarkable talents, it feels tragic to us that he would succumb to a desire to win at any cost. Dilemmas abound in this case, for Lance Armstrong himself, for the professional cycling world and the bodies that oversee it, for the charitable organization founded by him to raise money to fight cancer, and finally, for fans who find themselves torn, not knowing whether to criticize him for such a moral lapse or stand by him for his courage, accomplishments and contributions. Let’s take a look at a few of these.

Part 1: How he got into this mess

Why do people cheat? Dan Ariely’s latest book, The Honest Truth About Dishonesty, explores the slippery slope of rationalization that renders lying and cheating acceptable. Hardly a rational process, lying is strongly influenced by social and psychological forces. If we are surrounded by cheaters, if we feel justified to lie, it becomes easier to do so. Step by rationalizing step, Armstrong slid into the lie. He is torn between the desire to advance his own interest and win versus respecting common rules and honoring fair play. Recovering from life-threatening testicular cancer, he may have needed a boost. Most survivors of aggressive cancer treatment feel lucky just to return to a normal daily routine, let alone push their bodies to compete with the world’s top athletes! Where is the clear line between therapeutic drugs and performance-enhancing drugs? Does his health condition justify bending the rules? How much artificial assistance is defensible, and what is the likelihood of detection?

Figure 1. © Transcend Strategy Group 2012

Armstrong is not the first and won’t be the last to feel the intense draw of temptation; from the corrupting power of the dark side of the Force in Star Wars to the mythic tale of Robert Johnson selling his soul in exchange for mastery over the guitar, we are all too familiar with the archetype of otherworldly ability-at-a-cost. What are some of the options Armstrong might have considered? Following the noble path of Selflessness (upper left quadrant), while admirable, is not an easy choice for fierce competitors, and clearly Armstrong is that! Shooting for the upper right box where Self Interest and Common Good intersect may be ideal, but perhaps not a real option here. The lower left quadrant, Foolishness, looks at first like a nonstarter, but a moment or two’s reflection shows that it happens all too often: remember Tiger Woods and Michael Vick? The final option, the one he appears to have chosen, is to do whatever it takes to win. Morality aside, outright pursuit of self-interest can be risky. Get caught, and the price you pay will be high. Armstrong got caught and is paying a hefty price for not managing this dilemma better.

Part 2: The outside-in perspective: cycling world and fans

How do we judge the choices and actions of others? Which is more important, intent or outcome; difficulty or result; style or substance? Is it ever OK to do bad things to achieve a greater good? Who decides when it is acceptable to reset conventional boundaries of right and wrong? If you could have killed Hitler in 1938 before the atrocities of the Holocaust occurred, would you have pulled the trigger? If you could hide the fact that you or someone else did something like this, would you, or is it more important that they be held accountable for the crime they committed? It took anti-doping agencies over a decade to finally render a stinging judgment against Armstrong, prompting a lifetime ban on any further competing and the retroactive loss of his seven Tour de France titles. Legal complexities and costs aside, this must have been a tough decision to take, given the predictable consequences to the man, the sport, the many fans, and the cancer cause for which his foundation has raised over $500 million.

Figure 2. © Transcend Strategy Group 2012

This matrix looks at the dilemma from the perspective of the leaders of the eponymous Lance Armstrong Foundation. On the one hand, they will want to stand by the founder and through solidarity, preserve the integrity and value of the organization and its capacity to do good (the horizontal axis). But on the other hand, as evidence against Armstrong mounts, credibility and survival depend upon facing reality, and seeing that truth and justice prevail (the vertical axis). Where will they end up? The best outcome they can hope for at this point is a graceful exit and transfer of leadership (upper right quadrant). They have started down this path. Armstrong stepped down as head of Livestrong on October 17th. Time will tell if the organization and Armstrong can successfully transition allowing the great fund-raising and awareness-raising work to continue.

Part 3: How he deals with the mess he’s in

Lance Armstrong has announced he will not challenge or fight the charges. The emotional, reputational and financial costs are punishing (Forbes estimates his earnings in 2010 from endorsements and speeches were in excess of $17 million). While appearing to accept the verdict, he rejects its accuracy, stubbornly maintaining his innocence. He has just tired of trying to prove it. The operators of the Tour de France are so convinced of his guilt that they have decided not to pass along the title to any of the other top competitors from the seven years in question. Doping, they say, was rampant in the sport during those years.

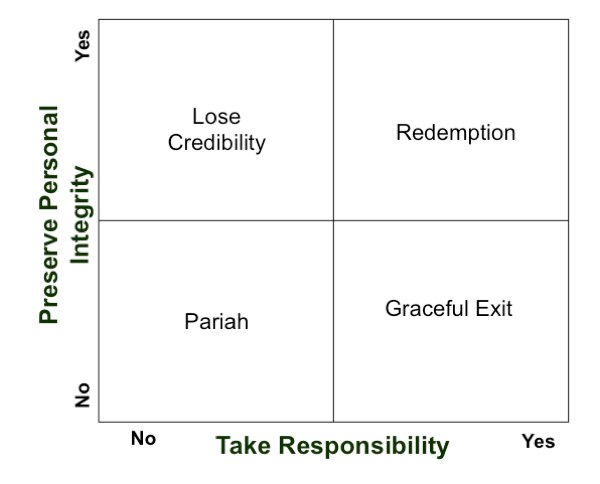

Figure 3. © Transcend Strategy Group 2012

How then should we depict Armstrong’s current dilemma? He has a great deal at stake, and at 41, many productive years ahead of him. We could look at money versus reputation, or, personal needs versus those of his charitable foundation. Globe and Mail reporter Hayley Mick has an interesting take on it (Armstrong’s dilemma: Fess up or shut up), looking at whether or not he admits to his guilt, when and how. In her article published on October 23, she follows the fates a number of other high profile figures caught in similarly embarrassing transgressions, some of whom were forgiven while others were not. Bill Clinton famously abused the power of his presidential office, then admitted his guilt through a very public and painful process, and in time returned to great popularity and prominence. He found Redemption. Baseball’s Barry Bonds and sprinter Ben Johnson both were found guilty of doping, both denied wrong-doing, and consequently, remain Pariahs who have not been forgiven. While Armstrong may be looking for a Graceful Exit, his refusal to take any responsibility for the mess he finds himself in is causing him to Lose Credibility, and become a Pariah to his charitable foundation and the sport he loves. Simply denying guilt doesn’t make it disappear. When you have been caught red-handed, it’s too late to cover up; you need to acknowledge the facts, take responsibility for your part in how things turned out, and swallow your lumps. Admitting guilt is not the opposite of protecting your reputation. It turns out it is the route you must follow if you want to recover it.

Send Comments to alex@transcendstrategy.com

Comments are closed.